Masquerades, performances by masked actors in plays, rituals, or dances, have a long history in many African communities. Masquerades vary between cultures and societies. The face masks displayed in this exhibition are only face-covering pieces that were part of a more complex masquerade apparatus, which also included headdresses, raffia, or other types of clothing for the body. In their original African context, the face/headpieces appeared in performances and rites always associated with the costume, as they functioned and made sense only together: the “mask” was the whole ensemble in the performance. This exhibition’s accompanying images and videos in this exhibition showcase these works in this context.

African performance is a tightly woven collection of arts. Many consider the concept of singing, playing instruments, dancing, dressing up, and dramatizing to be one and the same. The performing arts, the musical arts, and the dramatic arts are all thought of theoretically as being connected and working together.

Tabwa Buffalo Slit Drum, DRC, wood, brass, and cowry shells, JA-2006-03.

Bamana Ci Wara Headdress, Mali, TC-2015-18

Some spirits take on an animal form or deity, such as in the Ci-Wara or Chi Wara ceremony in the Bamana culture. Bamana peoples honor Ci-wara as the spirit who taught their ancestors how to till the earth and grow crops. The Bamana Crest Masks represent male and female antelopes, symbolizing the creative forces of nature and the cooperation necessary for successful farming.

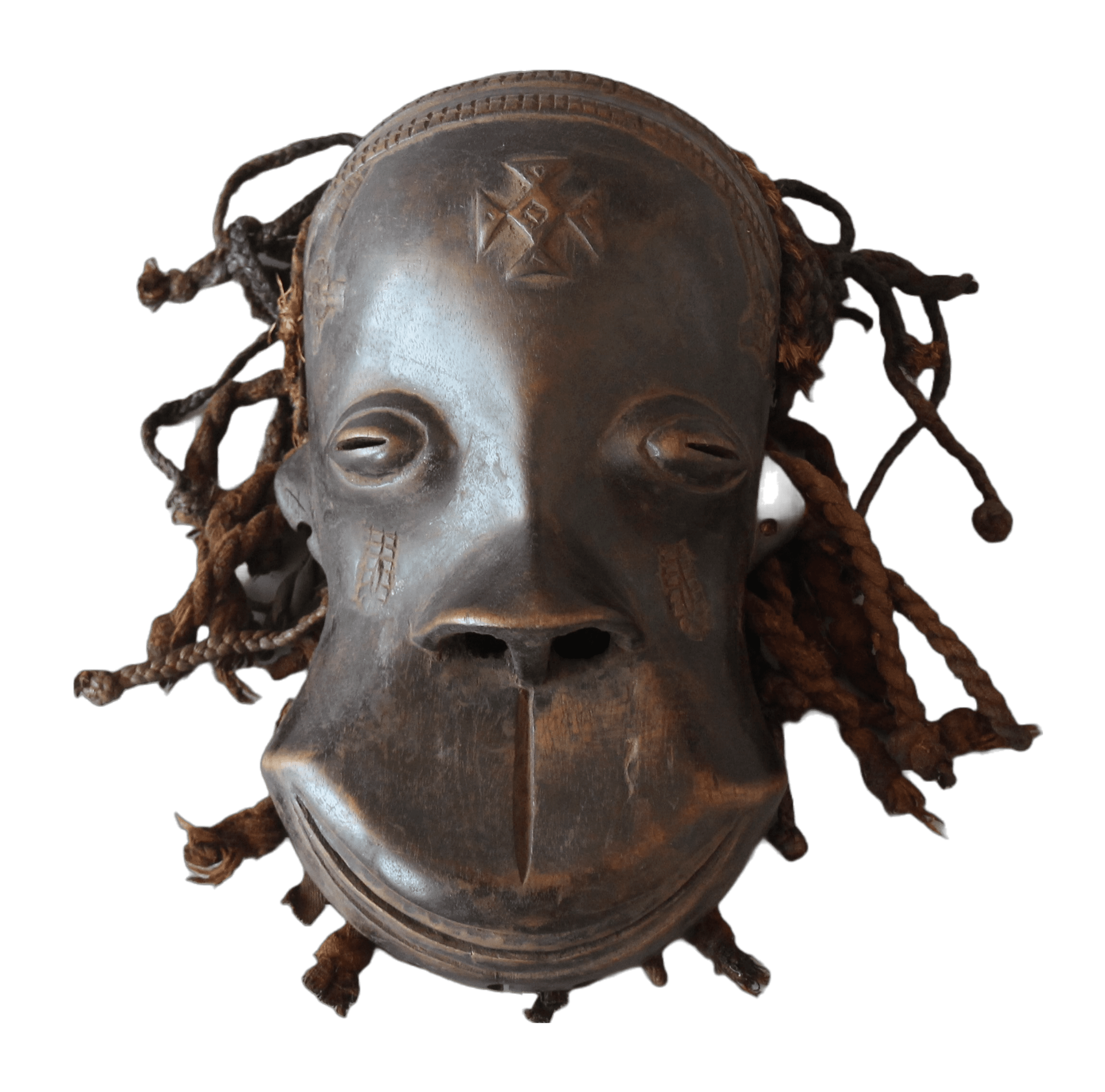

People in many cultures believe that spirits manifest as performers. The ancestral spirits of several tribes, such as the Chokwe of the Congo (Kinshasa), manifest during shows and ceremonies.

Chokwe Mask, DRC or Angola, JA-2015-02

Luba Mask, DRC, wood, fabric, feathers, JA-16-2018.

The colonization of Africa dramatically impacted the history and display of critical African objects. The meanings of objects are often altered, reinvented, and reconstructed when they are displaced and displayed in different contexts. Historically, displaying African objects in Western museums contributed to negative stereotypes that sought to justify colonialism. African communities in ethnographic collections were portrayed as traditional and frozen in a pre-modern, ahistorical time, needing cultural advancement. Over time, post-colonial studies has challenged the production of pre-conceived negative stereotypes of Africa, and anticolonial efforts in museum spaces have sought to better contextualize objects through the incorporation of more accurate information and histories.

While African masks informed European modernist styles of art, as can be seen in the art of Pablo Picasso, Europeans did not recognize African people for their modernity or creativity. Increasingly, African masks have been treated and displayed as works of art, but only focusing on aesthetics can equally negate their original context and meaning. These masks operate within complex systems of contemporary African aesthetics and performance.

Photo by Asiama Junior: Mohammed Blakk at Afrochella, CC BY-SA 4.0

INSTRUMENTAL AVATARS

Channeling Power Through Masks and Music

A Beatrice Anderson memorial exhibition.

The Department of Art presents

INSTRUMENTAL AVATARS

Performance, masquerade, dance, and music have played a significant role in African cultural expression for centuries. These art forms serve as a means of communication and storytelling, as well as a source of social and political commentary. This exhibition examines the ways in which performance, masquerade, dance, and music are used to express the beliefs, values, and experiences of peoples living in areas such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali, and the Ivory Coast.