A Mellon Graduate Assistant Performance

Opportunities often arise suddenly, and it is not always clear where they will take you.

Two days before Thanksgiving 2021, an email came through from Dr. Robert Luckett, Director of the Margaret Walker Center (MWC), offering me a graduate assistantship connected to an Andrew W. Mellon grant the center had received. “Let me know what you think. We can think about what might be a good MWC deliverable.”

Dr. Luckett had been advising me on an independent study at the historic Wolfe Studio focused on cataloguing eighty years’ worth of archive worthy correspondence, photographs, drawings, and documents.

The Mellon Graduate Assistantship would continue this work with a small stipend. “I’d appreciate clocking that time, and know that producing a MWC deliverable would enrich the experience. Please put me down for that and maybe we can begin to mull that deliverable when you’re on site Dec. 2nd.”

All partnerships bend the work toward them in a way.

With this graduate assistantship on the horizon, I began to look at the developing Wolfe archive for where there might be connecting points. How might this art studio in Northeast Jackson surrounded by the most affluent neighborhoods in the city intersect with the Margaret Walker Center on the West Jackson campus of Jackson State University, one of the largest HBCU’s in the United States?

At our December 2nd meeting, I conferred with Dr. Luckett about my developing thesis topic based on the primary documents catching my attention. Karl Wolfe, a portrait artist, had written a memoir published in 1979 aptly titled Mississippi Artist: A Self-Portrait. In the book, Wolfe spends an entire chapter on an account of his time in conversation with Dr. Laurence C. Jones while painting his portrait in 1952.

I was captivated by this portrait commission.

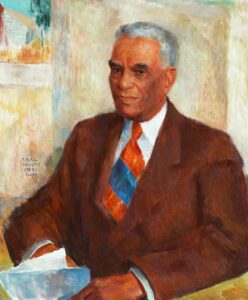

Karl was a white working-class artist in the segregated South who made most of his income painting portraits of the white elite. Karl’s writing details Dr. Jones’ sitting for the portrait in his studio over multiple sessions two years before Brown vs. Board of Education overruled the ”separate but equal” precedent of Plessy vs. Ferguson. Karl’s papers included a number of drafts for his memoirs and other documents associated with Dr. Jones. This section of the archive seemed ripe for exploration.

Dr. Jones was the founder of Piney Woods Country Life School in Central Mississippi and had long been a fascination of mine. Born in Missouri in 1883, Dr. Jones had graduated from the University of Iowa and felt called by God to teach in the South. Enduring a great deal of hardship along the way, a series of serendipitous events led Jones to the Piney Woods region of Mississippi where he began teaching under a cedar tree. Those small outdoor classes grew into a sprawling campus which sustains through today. Along with a few other books and letters I found among Karl’s manuscript notes, it seems Dr. Jones was a fascination we both shared. Dr. Luckett remarked that the Margaret Walker Center archive held an oral history recording with Dr. Jones.

I had found an intersection to begin my journey.

After re-reading the Dr. Laurence Jones chapter, I emailed Alissa Rae Funderburk, the Mellon Oral Historian at MWC, to access the Dr. Jones interview. The Margaret Walker Center Oral History Division holds 68 oral histories in its’ Piney Woods Country Life School collection. Gathered in 1979 by Dr. Alferdteen Harrison, these oral histories cover a range of topics including superstitions, integration, inter-racial and intra-racial discrimination, and auxiliary groups such as the Rays of Rhythm and the Sweethearts of Rhythm Band. Dr. Jones interview came in two parts; the audio of the first part is digitized (you can hear Dr. Jones voice!) and the second is available as a transcript.

I realized that it was a necessity to get on the ground at Piney Woods. As luck would have it, the MWC Archivist Angela Stewart had been the archivist for Piney Woods School prior to joining the MWC team. With Angela as my guide, we hopped on the road one morning in March to visit the school.

Perhaps illustrative of the wanderer in me, we showed up unannounced with no meeting and no point of contact.

Following strict covid protocols, security allowed us on campus to visit Dr. Jones gravesite next to the original cedar tree and log cabin which had served as the first classrooms on the land. Seeing the cabin was an excellent reminder of how important physicality can be. No image can prepare you for the cramped quarters in which the first Piney Woods students met for class each day, certainly thankful nonetheless for having moved out of the elements. Thanks to the intrepid Ms. Stewart and her familiarity with the campus, we were able to duck into the administrative building for a brief moment to see the portrait which had brought the two men together 70 years prior.

On the trip, Angela shared an intersection in the work with me I’d likely have never found on my own.

In response to my remarking on how beautiful and peaceful the land was, Angela shared that Margaret Walker would occasionally retreat to the Piney Woods campus to write. She recalled a specific journal entry in which Margaret described her experience of the Piney Woods land. On that occasion, she had been working on her autobiography. On our way home we stopped at The Donut Shop & Bakery on Highway 49 for porkchop sandwiches and I dashed off an email reminder to Ms. Stewart to send me the link to that entry.

Monday afternoon, March 20, 1973

“It is very beautiful here – quiet and peaceful with lovely trees and shrubbery everywhere. I look out of my bedroom window and see beautiful trees everywhere.” In the margin is a list running vertically up against the metal spiral, “sweetgum sycamore oak elm pine magnolia Flowering Judas.” Margaret followed this with a quick and surprising report, “Piney Woods is threatened by a lake of gas and sulfur directly under the school grounds. Shell Oil is on the campus and already they are predicting the campus may have to move.” I’m happy to report Piney Woods is still as beautiful and peaceful as Margaret’s account, surely thanks in no small part to the wisdom and stewardship of Dr. Jones who was still alive (but 90!) at the time. From here, Walker dove into memories of Richard Wright and his encouragement and advice on publishing her poetry.

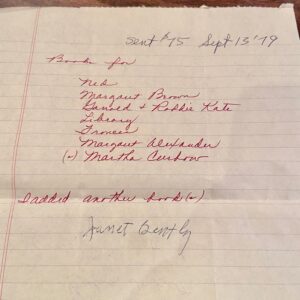

A few days later I ran across a page in Karl’s pile of manuscript notes dated September 13, 1979.

Wolfe was ordering copies of his own freshly published book to share with others. On the list – Margaret Alexander. I can’t truly know if this was the same Margaret Alexander, but as a researcher combs an archive, it’s these glimmers of possibility which make your hair stand up. I’d made a little circle, mostly meaningful to me on my little journey. Maybe each of these people had some form of relationship with each other. Certainly it seemed passing. Perhaps Karl simply wanted to share his own work with a writer he admired. I’ve yet to see where either Dr. Jones or Dr. Alexander ever mentioned Karl Wolfe. But to be able to draw some semblance of a line between the three of them while working for the Margaret Walker Center and Wolfe Studio here in 2022 feels meaningful.

In 1981, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History commissioned Karl to paint a copy of his Dr. Jones portrait to hang in their Mississippi Hall of Fame gallery. There are subtle differences, the most meaningful probably being the slight shift of the eyes so that Dr. Jones now looks directly at the viewer. The difference in the boldness of the colors may simply be a result of their differences in age and the preservation capabilities of each institution. I like that Karl prominently wrote “copy” on the portrait for the Old Capitol, ensuring that anyone who might question it would know that the one held at Piney Woods is indeed the original.

On this journey in the archive made possible by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, it is the intersections which most captivate me.

How did the lives of two artists living in Jackson, MS – one a portrait painter, the other a poet – intersect? Born 12 years apart and both living into their early 80s, in what ways did this white man and black woman living through the Jim Crow South manage to have anything in common? At the very least, they were both attracted to and impacted by experiences with Piney Woods and Dr. Jones. This is evident in the archive…and I’ll spend some time yet reflecting on what that means to me today.

Skip to main content

Skip to main content